A call for the decentralization of (biotech) innovation

Can you and I build a truly disruptive biotech startup in LatAm?

Boston and the Bay Area are the cunas of biotech innovation and entrepreneurship. Sure, there’s also Toronto, Austin, Beijing, Paris catching up, and interesting things happening in England too.

However, as a Mexican bioentrepreneur-wannabe, I have a deep, somehow emotional question: can I build a truly disruptive (biotech) company in LatAm?

This post is my first attempt to answer that question. I use the book Zero to One as a reference for mindsets and case studies of LatAm unicorns and biotech startups in the region in order to draw hypotheses.

Please know that I’m hungry for feedback and want to hear your thoughts. Thank you in advance for reading!

1/ A truly disruptive (biotech) company

Are you a 10% or a 10x?

My grandfather once told me how Mexico (the place I call home) opened its doors to global commerce until the 80s. He witnessed how imported goods were not only cheaper but also better and how that created a ripple effect that helped Mexico’s economy grow.

Then I wondered: why does Korea have a “Korean Apple” (Samsung) but we don’t? Even when we are neighbors to the country where things happen!

As someone who worked in the telecoms industry for over 40 years, grandpa told me that it was the so-called ‘know-how’ and culture. The difference didn’t end in lack of good education. While China was building isolated factories for workers to focus on doing the job, Mexico wasn't.

Yet that wasn’t really my burning question. What I really wanted to know is why nothing insanely great seemed to be invented here. Why Apple, or the future for that matter, isn’t born in Mexico.

In Zero to One, Peter Thiel mentions the difference between innovation by globalization and 0-1 innovation. That is, transplanting ideas into a different context or changing the game all-together, making a 10% increase versus doing things 10x better.

For instance, CRISPR-Cas9 was 0-1 while prime editing could be seen as globalization, organic milk is 10% better whereas lab-grown milk is 10x better, the iPhone was 0-1 and many of its processors have been transplanted innovation .

A reason to try

Great things happen only once. Innovation is the quasi-magical act of bringing something new into the world, something that wouldn’t exist if it wasn’t because of human ingenuity and determination. Entrepreneurship then, is giving millions, perhaps billions of people, access to that invention—Sofia being too romantic on entrepreneurship.

After reading “the bible of startups”, I started to hate the idea of being a globalization-kind of entrepreneur. Why would I even try to build something that has already been conceived by someone else? That feels like trying to give birth to the clone of a baby that is already in their mother’s arms.

The answer lies in whether I want to be an innovator or an entrepreneur. At least 8 search engines had been born before Google. The miracle thus, was not in the idea or the invention, but in the execution: the “take it into the hands of billions” part.

So why don’t the brightest minds in each company join forces just like Musk and Thiel did with PayPal? I want to guess it’s not a matter of ego but the genuine and relentless belief that they have a better approach—so it makes sense to optimize for variety by testing multiple hypotheses in parallel.

Now I’ll try to answer a bit of the initial question: does it make sense to try to bring lab-grown cotton into the hands of billions? Even if someone else is already trying? Even if my approach is only slightly different?

Yes, Sofi. It makes sense because no one has nailed it yet. You go test something different.

2/ In LatAm?

Capital, talent, supply chains

Places with top unis tend to be innovation hubs. They not only create a talent pipeline for those already-established companies, but they also enforce a positive feedback loop for new startups to be born and raised there.

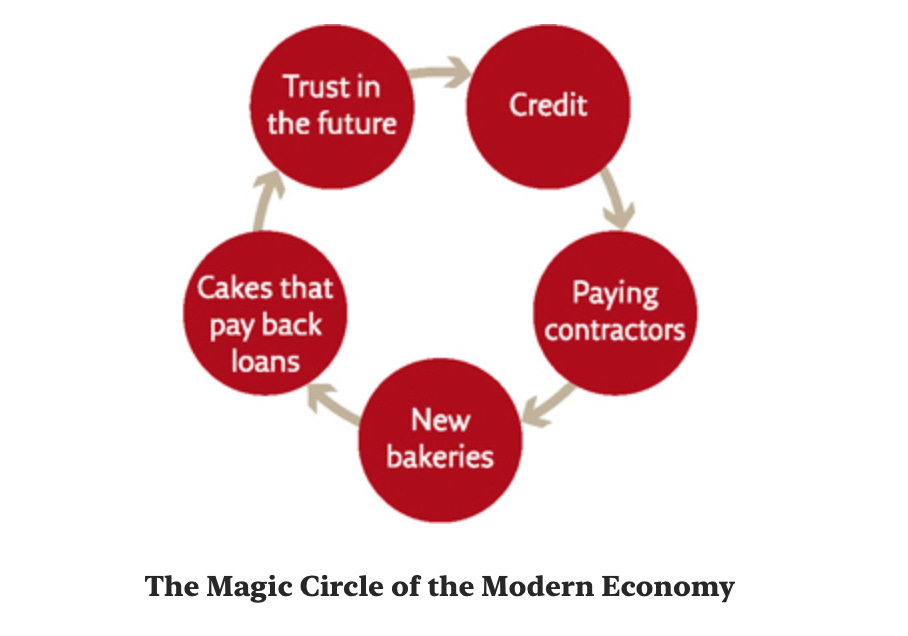

Indeed, that magical act called innovation needs money put into research, education, and venture creation. For these are all long-term investments, faith in a better future and trust in the teams that create it, is essential.

The next question then, is whether Mexico can afford “trust in a better future”. On the public sphere, corruption and poor administration make it hard to get funds for research and education. On the private sphere, my hopes are in VCs and universities that can supply talented and relentless individuals.

Julian Rios, founder and CEO of Eva, has admittedly been quite a compass for my journey these years. When I asked why they were building in Mexico when they could be anywhere else, the answer was that this is where they can have the greatest impact.

Capital doesn’t seem to be a problem, since they’ve actually raised millions from world-renown funds including Khosla Ventures—though I actually gotta ask him why their investors think it’s a good idea for them to build here.

Julian thinks that the hardest part of building startups in Latin America is finding talent, which makes sense to me up to a certain point. While the number of Bioengineering BS graduates is only increasing, most of them are either going into grad school or getting a job at multinationals like Pfizer or Bayer or national food companies. Perhaps they don’t want to take the risk of working at a startup?

Another fact to consider is that Eva is in the digital goods sector and supply chains get more complex when you’re building physical goods. Whereas ordering DNA in the US may already be everyday business, it will take months for your shipping to arrive here. I once ordered a kit from FreeGenes (an initiative by Stanford Professor Drew Endy) and my package never made it out of customs office.

Fortunately I haven’t had any issues when ordering reagents to grow cotton in-vitro; the supply is here. However, I wonder how that could look like when I start using larger quantities to scale up or thinking farther in the future, when I want to export my products.

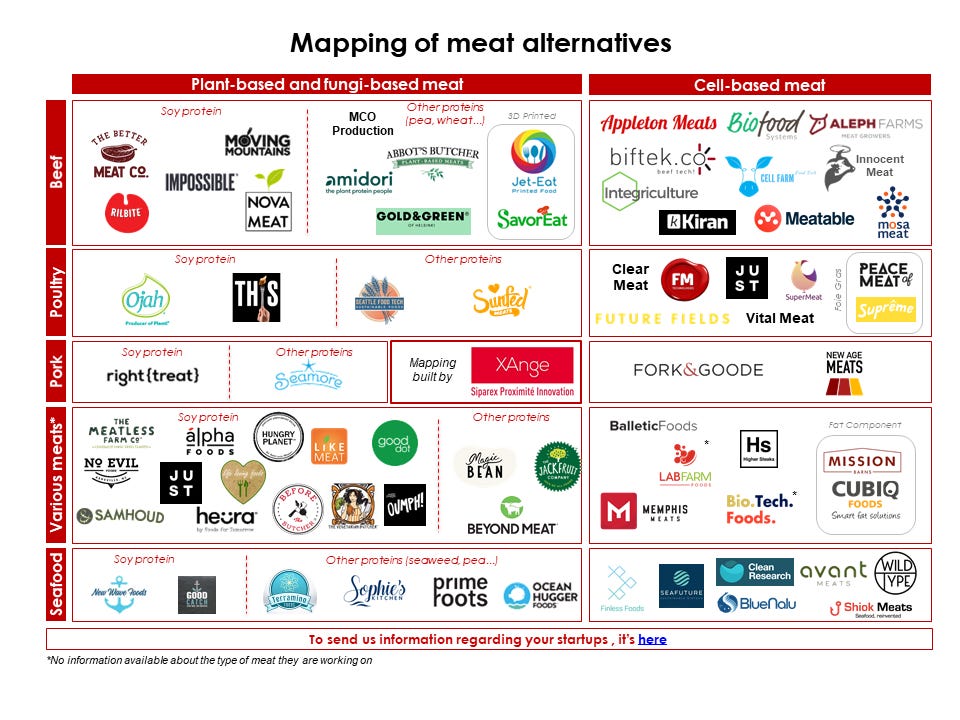

See, the only big company building plant-based foods in Latin America is NotCo. Though they’re in the future of food sector, we need to consider how they could be different to a cellular agriculture startup:

Talent: a big part of their innovation lies in their AI platform. Anywhere in the planet today, it’s way easier to hire a software engineer than it is to hire a tissue engineer. Then their manufacturing process is not that different to any other processed food so talent is findable.

Supply chain: I assume that the reason they’ve scaled up relatively fast is because the natural ingredients aren’t very hard to get. At least not as hard as special growth factors.

Building any startup, let alone one that involves innovation of any kind, is a super challenging endeavor. Even when Beyond and Impossible were already doing something quite similar before, the fact that NotCo is already selling their products in over 8 countries is outstanding and should definitely be celebrated.

The LatAm → US startup pipeline

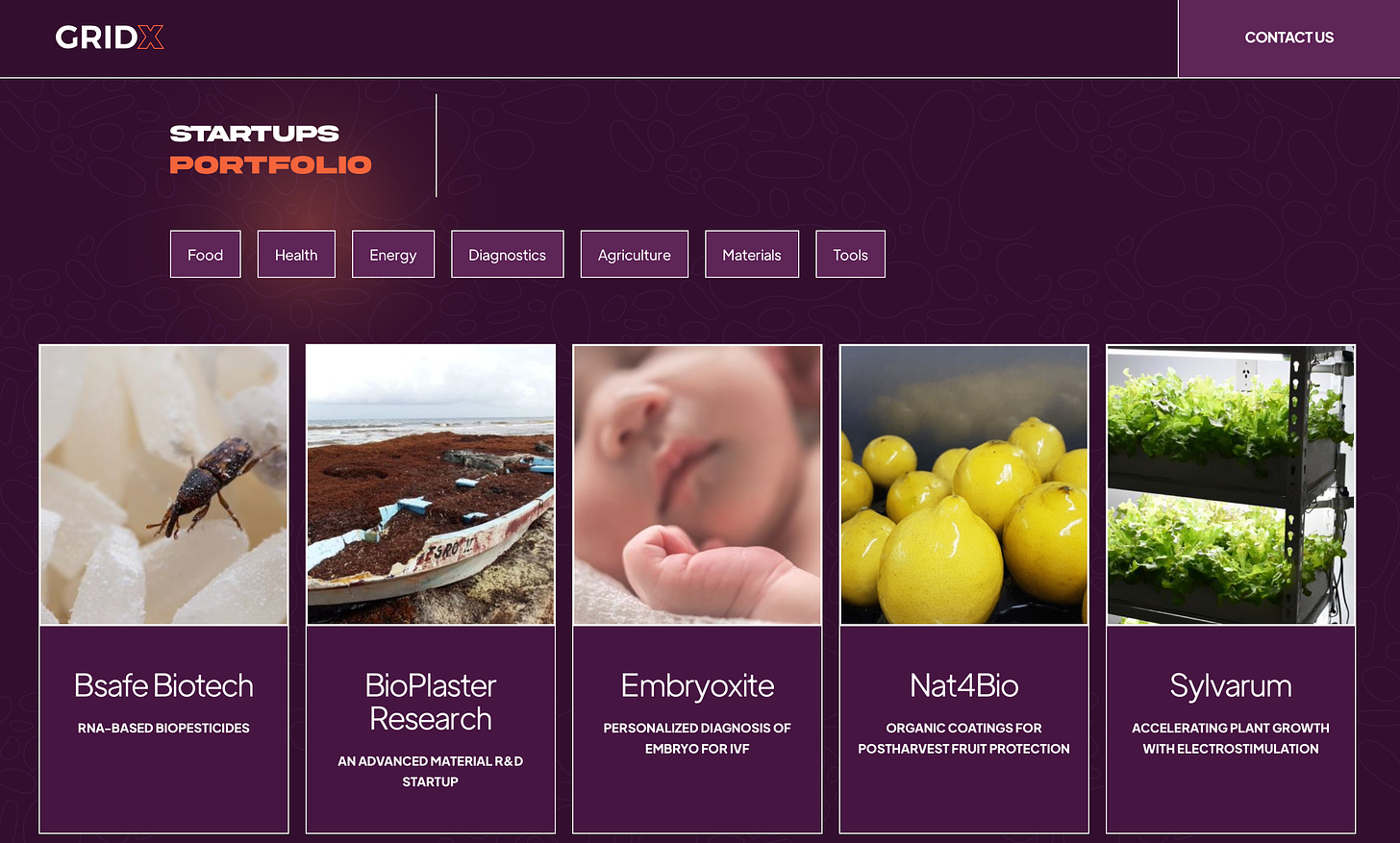

What about the NotUnicorns? I truly admire GRIDX, LatAm’s only accelerator focused solely on biotech startups. Their portfolio is composed of startups in the materials, food, health, energy, diagnostics, and agriculture industries

Some are 10x, others 10%. An important point to consider is that at this point in biotech, no one can for sure be a multinational monopoly yet. So again, I think that testing different hypothesis in parallel is something we need as humanity to increase our odds of solving the world’s biggest problems.

GRIDX startups are proof that building biotechs in LatAm is possible! But it’s not enough to answer my question. You know, GRIDX can first invest up to USD $200K in pre-seed and then connect those startups to other funds. In fact, startups like Michroma, AgenTAG and GALY started in LatAm and then initiated operations in the US too. Some of them enrolled in programs like IndieBio and received capital from US investors.

That tells us that the answer to my question is not that black and white after all. A strategy that some are following is to start here and then establish another base in the US. Interesting.

GTM for CellAgs

I still want to make the point though, that anyone who wants to build a cellular agriculture company in LatAm can face quite some different challenges and there’s only 1 cellag startup in GRIDX’s portfolio.

These challenges may depend on the kind of product one is building through cell ag. Most food tech companies are following a B2C or B2B2C model. They’re cutting supply chains by selling directly to wholesalers or retailers, sometimes even directly to consumers, as JUST is doing in Singapore.

Textiles like cotton however, are a raw material that is later on turned into clothes, clothes which are mostly produced in China or India which (logically) also happen to be the largest cotton producers worldwide. All cotton producers are B2Bs.

Even if we succeed in producing cotton in a Petri dish and then scaling it up in huge bioreactors, I wonder if fashion brands would like the idea of shipping cotton to the other side of the world. Would it make ecological and economical sense? Would it be reliable? What infrastructure barriers could we face in Mexico?

What if we followed another go-to-market strategy?

What if we expanded our value chain to manufacture clothes here too? Do we now have the so-called ‘know-how’ for that? Will it be as cheap? Can we automate it more than China? I mean, even though China occupies over a third of the clothing market worldwide, the US still has 17% and it’s a big enough of a market…

What if instead of building lab-grown cotton per se, I focused on building the method so it can be licensed and built in any other part of the world in a decentralized way? Is that realistic? Would that be sort of “I sell you the IP and charge you for installing the factory over the period of 2 years”? Is that scalable? Who is our client?

The foundry model

Understanding those challenges has led a trio of former Latin American iGEMers to create iGEM Design League (iDL), an iGEM division that focuses only on the design phase of the synthetic biology cycle and operates in LatAm only. Students start by identifying a problem, then they match it with a potential synbio solution and finish by designing their genetic circuits and doing some math modeling for their future experiments.

In its inaugural year iDL landed a collaboration with Ginkgo Bioworks. The idea was for the winning teams to travel to Boston to visit Ginkgo’s foundries and potentially get their products manufactured by them.

If the foundry model succeeds, it will mean anyone can build with biology, anywhere. As for now though, it might be too early for iDL teams to grow with Ginkgo, whose clients are mostly bigger companies established in the US.

I wonder if Ginkgo is taking CellAg startups…

3/ It all goes back to your mission, to the problem you want to solve

Never did I say that startups doing globalization were better or worse than 0-1 startups. I believe that a 10% improvement is better than no improvement at all. I think that some founders who transplant technologies—into a market that hasn’t been penetrated yet—do so because they think their better understanding of the market will provide at least 10% more value.

There are currently 8 Mexican unicorns and almost 50 in the LatAm region. Most of them are fintech and e-commerce “globalization” startups like Bitso. Though the idea is not new at all, Bitso is building something that thousands of people want: a platform to sell and buy cryptocurrencies in Mexico, in an easy and secure way. Their value prop and addressable market are real. They have brought value into the world.

After cancelling my enrollment to UC Berkeley—yes, I still think about that sometimes— I thought I might just set myself up for a different mission: “what if I can make a difference here? What if more bio developers, including myself, can catalyze the biotech revolution in Latin America?“.

Today, it’s exciting to know that I won’t be alone in this journey. I’m now confident in the bold and smart LatAm biotech founders out there, building amazing things. Regardless of their valuation today or where they decide to build tomorrow, I think it’s possible to start a biotech in LatAm that impacts billions.

Perhaps lab-grown cotton is not the the startup I’ll build for the next 10 years. What I want to do for now though, is to try. I want to bring extraordinary things into existence and… another update might just pop into your inbox in case I choose to take one of those things into the hands of millions.

You can also find me on Medium, where I write about exciting technology. Or listen to my conversations with world-class biodevelopers on any podcasting platform!

I appreciate I am late to the party.... but this was a really interesting read. We have a similar centralised biotech space in the UK (between Oxford, Cambridge and London)

In terms of scaling enough for global production and bringing down the unit cost of a fermentation produced product is an issue that can be debated until the cows come home! It very much depends on your plan but now there is more calls for materials to be integrated into a circular economy so could you work this in. Would you take back waste products and offcuts etc.

But very cool stuff happening in the space and its great to find another like minded individual !

From the Indigenous complexity, greetings, sibling!

Since we chatted a couple of months ago, I have been reading some of your writings and ideas. They are pretty insightful and informative, which makes me glad that you are staying in your home to understand its capacity and relation from a within-analysis (inside-the-box instead of outside-the-box)perspective.

Apya Yala (LaTam/SA) has an unorthodox talent that one tends to underestimate ther capacity and relation to the environment where they have created kinship and practice Indigenous Biotechnology, science, and technology; classically trained “experts” are exploring climate adaptation and mitigation.

Apya Yala’s talent will undergo a resiliency bio-capacity development from their/our motivations. Still, we need to get away from the way, meaning approaching talent not from the “ego” to solve “the” problem but rather from an “eco” bioculture design that creates the conditions for talent to emerge.

Thank you for your ideas, and I look forward to the unexpected outcomes of your influence on many! I hope our Apya crosses to kollab:)