Scientists

Can evolution explain gender discrimination? Who are outstanding women in the life sciences? How big of a problem is gender discrimination in biotech today and what should we all do about it?

I’ve never been into activism of any kind because it implies that I’m not in complete control of things; that I have to speak up so someone else hopefully listens to my needs and does something about the situation.

As a young woman doing science in the 21st century, I feel deeply fortunate about living in a time when I’m not deprived of college education, a time when I can tweet ideas and be listened to by people who I admire, and most excitingly, a time when being a woman founder in the biotech space is even a possibility.

Still, I certainly cannot speak for every female scientist or say that I’ve never been discriminated against for doing science as a girl. For I can share tweets that are only about science, I can also read fellow women scientists’ experiences with gender discrimination at their universities, with investors and at conferences. For I’ve so far had amazingly supportive women and men mentors, I’ve also heard the naysayers.

As said before, I would hate to sound like an activist and I’m a little tired of hearing the same 3 words “women in STEM”. So in this post, I just want to answer some questions for a fellow *scientist: does gender discrimination have an evolutionary basis? Who are some cool women who’ve done life sciences work in the past and today? With hard data, how big of a problem is gender discrimination in biotech today? Is discrimination the only reason why there are more male scientists than women scientists? What should we do about it?

*Just like the cool people I’ll tell you about, that scientist just happens to have 2 X chromosomes in her 23rd pair.

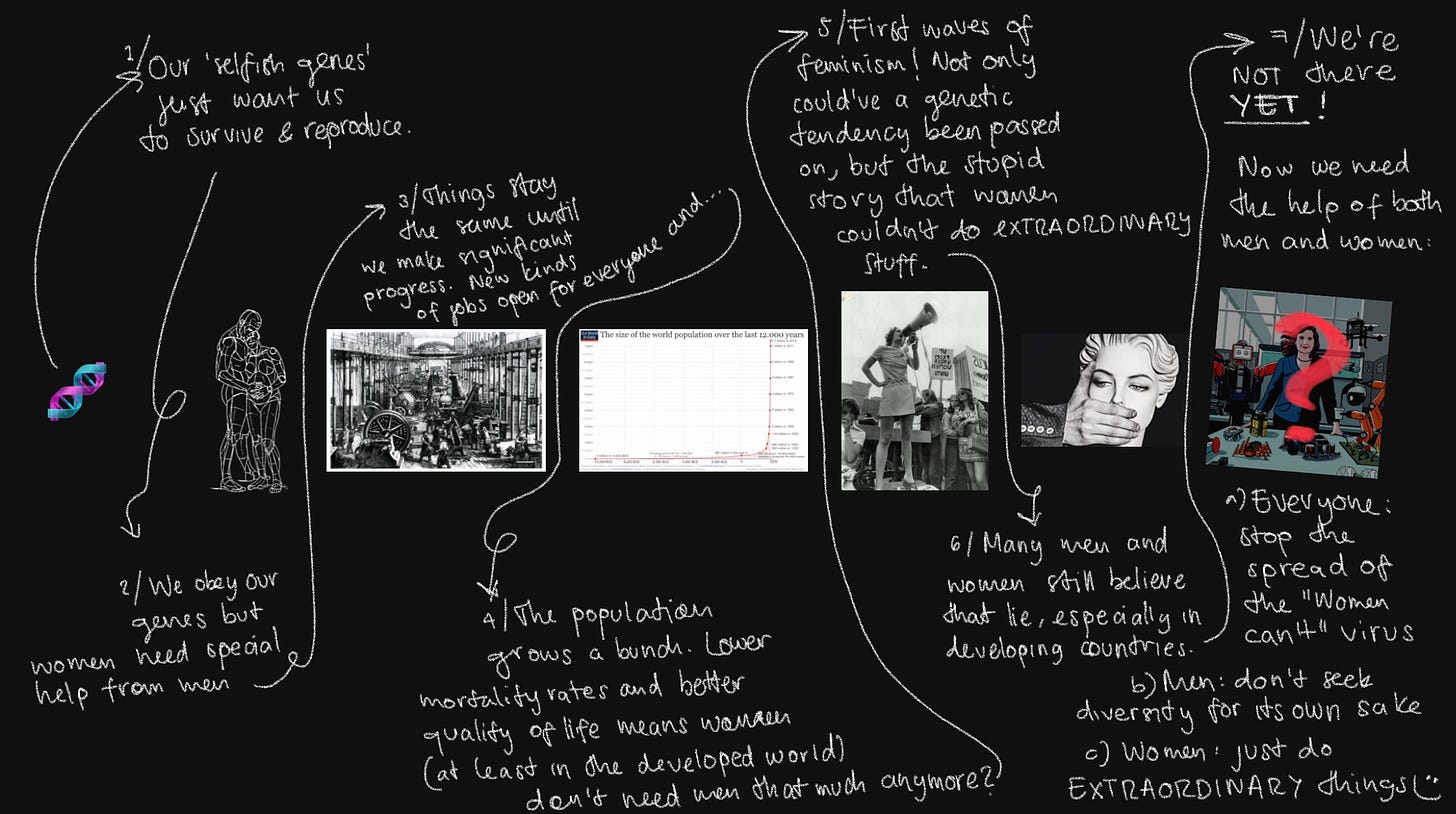

Blame evolution?

If this were a matter of physical strength, why have women been historically forbidden from activities like science or poetry and forced to do household jobs? If all-all-black workforces were controlled by all-white management, why couldn’t an all-male soldiery be controlled by at least some women? If women are often stereotyped as more persuasive and collaborative than men, why isn’t history full of excellent women empire-builders?

Theory #1

In his book Sapiens, historian Yuval Noah Harari explains two theories that personally make more sense. The first one suggests that both men and women want to pass on their (selfish) genes. Pregnancy put women in an especially vulnerable position so they needed men who could do the hard physical work. In exchange for that, women adopted the role of caretakers which deprived them from practicing their physical and socials skills as much as men.

I think there’s something that theory misses: some stories can last longer than genes. Not only did women develop a tendency to get out of the way when it came to hunting dinner. Throughout generations, both women and men came to believe fake news like “girls can’t do science”. Those fake news became embedded in our societal believes which many men and women sadly hold to date.

Theory #2

Yet another question to ask about theory #1 is: if animals like elephants and chimpanzees have managed to create female networks—because or despite of having to take care of their offspring and being physically weaker than males—why hasn’t that been the case for us humans?

Yuval says that our greatest strength as Homo Sapiens is not our IQ and certainly not our physical strength either, but our ability to cooperate in large groups. The second theory then, suggests that male are simply better at cooperating with each other. Their superior social skills allowed them to form networks just like female elephants and chimpanzees do… except this became a patriarchy that worked against women?

If theory #2 is true, it means that throughout most of history, men’s social skills allowed them to be the rulers and keep on telling the story: “women can’t do science, women should stay at home”.

Then in the late 19th century 3 trends started to arise: the first feminist wave, the second industrial revolution, and the start of an exponential increase in the human world population. Might these happenings be intertwined, in some way?

While there are examples of women who did scientific work as early as the scientific revolution, they seem to be quite an exception. My observations tell me that it wasn’t until the second industrial revolution that the exponential drop in mortality rates and economic growth could’ve allowed for feminism and for the first “women in STEM”.

Beyond Curie

Call me ignorant but the only renown women researchers I’d heard of before writing this post were Marie Curie, Jennifer Doudna, and Rosalind Franklin. I strongly believe that if we want to break the millenary stupid story (“women can’t [insert whatever]”), we need to tell more stories of women who have done extraordinary things.

As a bioengineer in-the-making, I was especially eager to learn about more women scientists who made spectacular life sciences discoveries. These 10 outstanding women were medical doctors, crystallographers, biologists, biochemists. They left invaluable stepping tones for the next generation to build upon.

1. Nettie Maria Stevens (1861-1912)

Though her earliest research was in protozoa morphology, she couldn’t be more relevant to this article: Stevens discovered sex chromosomes while studying the mealworm. She found that the males made reproductive cells with both X and Y chromosomes whereas the females made only those with X.

Apparently, this great researcher had to switch between long periods of work and study, which led to a late start in her career (at age 39). In contrast with the Annus Mirabilis observation—which says that the most productive year of great scientists is before age 40—the next 11 years were the most productive of her professional career.

She passed away due to breast cancer at age 51. Could she have made many more contributions if only she’d received more support earlier and not died so young?

2. Alice Augusta Ball (1892-1916)

She was the first woman and first African American to receive a master's degree from the University of Hawaii and the first female chemistry professor at the university.

This rockstar scientist cured leprosy at age 23. Said elegantly, she developed the "Ball Method" which was the most effective treatment for leprosy during the early 20th century. Her technique involved isolating ethyl ester compounds from the fatty acids of the chaulmoogra oil.

I was shocked to read that she died just 1 year after that, at age 24. A newspaper article suggests she may have been poisoned with chlorine during one of her lectures.

3. Barbara McClintock (1902-1992)

Dr. McClintock produced the first genetic map for maize, demonstrated the role of the telomere and centromere, and was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for discovering jumping genes.

Her mother didn’t want her to go to college for fear that she would be “unmarriageable” but her father stepped in and she started her studies at Cornell's College of Agriculture.

At some point, she decided to stop publishing due to skepticism of her research. In reference to that, she wrote:

Over the years I have found that it is difficult if not impossible to bring to consciousness of another person the nature of his tacit assumptions (...) This became painfully evident to me in my attempts to convince geneticists that the action of genes had to be and was controlled. It is now equally painful to recognize the fixity of assumptions that many persons hold on the nature of controlling elements in maize and the manners of their operation. One must await the right time for conceptual change.

I find a couple of things interesting about this: first, I wonder if it was just simple skepticism or gender bias 🤔 and second, it’s fascinating to notice how timing of discovery can play a role even within the scientific community! The latter is definitely a topic that I want to explore on its own in another article.

4. Dorothy Hodgkin (1910-1994)

In this story, it was Dr. Hodgkin’s mother who first encouraged her and her sisters to pursue their passions, starting at the early age of 10 and when she fought to study at Oxford University, becoming one of the first people in the world to study organic compounds through X-ray crystallography.

Dorothy advanced this technique to determine the structure of biomolecules like penicillin, insulin, and vitamin B12, for which she became the third woman to win the Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

Developing rheumatoid arthritis at age 28 didn’t stop her from doing the delicate experiments she wanted to. Hence that it’s beyond mind-blowing to me how we now have tools such as liquid-handling robots and protein structure predicting softwares that we could just play around with in our garages if we wanted to. How amazed would Dorothy be? What would she not want to do with these 21st century superpowers?

Well, she was part of getting up to this point in science.

5. Ruth Rogan Benerito (1916-2013)

Also known as a bioproduct pioneer, Ruth was a chemist and inventor who developed wrinkle-free cotton fabrics, which reinvented the cotton industry after World War II. The treatment consisted of inserting short organic molecules between the cellulose bonds in order to strengthen them.

Some other cool facts about her are that she held 55 patents, started college at age 15 and once taught a driving course even though she’d never driven a car before!

"I believe that whatever success that I have attained is the result of many efforts of many people. My very personal success was built from the help and sacrifices of members of my family, and professional accomplishments resulted from the efforts of early teachers and the cooperativeness of colleagues too many to enumerate."

As a female innovator, I think it’s worth highlighting how important support networks were for Ruth, something I will touch on later in this article.

6. Esther Lederberg (1922-2006)

Professor Esther discovered the λ phage and the bacterial fertility factor F, and furthered the understanding of the transfer of genes between bacteria. Textbooks often attribute her accomplishments to her husband.

First intended to study French or literature in college—and discouraged by her teachers to pursue anything scientific—she completed a Masters in genomics at Stanford, where she was later on invited by professor Stanley Cohen to become the curator of Stanford’s collection of plasmids, which basically entailed naming a lot of them.

7. Tu Youyou (1930-present)

Scientists worldwide had already screened over 240,000 compounds without success when Tu had an idea of screening Chinese herbs. That’s how she discovered artemisinin and dihydroartemisinin, saving millions of lives in South China, Southeast Asia, Africa, and South America from malaria.

Not only that, but she also volunteered to be the first human subject, which she thought of as a moral responsibility. Later in 2015, she was awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine.

As a side note, she did that with no postgraduate or abroad studies.

8. Ada Yonath (1939-present)

Along with two of her colleagues, this Israeli crystallographer received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for studies on the structure and function of the ribosome. That turned her into the first Israeli woman to. win the prize, the first woman from the Middle East to win a Nobel prize in the sciences, and the first woman in 45 years to win the Nobel Prize for Chemistry.

She went to school in her home country until she accepted postdoctoral positions at Carnegie Mellon University and MIT.

9. Flossie Wong Staal (1946-2020)

Originally from Hong Kong, she was a virologist and molecular biologist first to clone the HIV virus and map its entire genome.

Although no women in her family had ever worked outside the home, let alone studied science, her parents supported her academic pursuits when she had the opportunity to study bacteriology at UCLA.

Interestingly, she’s also the first women founder in this article, having founded the biopharmaceutical company Immusol with her husband, neurologist Jeffrey McKelvy.

10. Elizabeth H. Blackburn (1948-present)

Elizabeth received her PhD in 1975 from Darwin College at Cambridge University, where she worked with Frederick Sanger developing methods to sequence DNA using RNA.

She was doing postdoctoral research at Yale when she noticed unfamiliar tandem repeats in Tetrahymena thermophila, which. turned out to be the telomeres. She went on to discover the enzyme which created them (telomerase), and won the Nobel Prize with her colleague, Carol W. Greider, for their contributions.

Blackburn was appointed a member of the President's Council on Bioethics in 2002 but was dismissed shortly in 2004, likely due to her support to human embryo research (which the Bush administration was opposed to). Lots of people, including 170 scientists, disagreed strongly with this decision, indicating that some balance on such advisory bodies is needed too.

From doing groundbreaking research in Sanger sequencing as a PhD student, to holding her beliefs in bioethics, Dr. Blackburn’s story seems incredibly unique to me.

11. Perhaps you?

I admittedly had to do some research to tell you these stories. Yet, that doesn’t mean that there aren’t contemporary, outstanding female scientists who have inspired me in my journey so far.

Christina Agapakis is top of mind. One of the creative minds at Ginkgo, with a history of unique projects… like making cheese out of bacteria that collected from human microbiomes! I think authenticity is the greatest value I’ve learned from her.

Then, I’ll always remember Laura Mayorga as my first-ever mentor in the field, the first person who believed in me and helped me grow my critical thinking so much when I was researching CRISPR applications in diabetes. She recently received an award by 3M for being one of 25 top female researchers in Latin America!

Subaita Rahman, a college student who co-founded Nucleate Dojo, the Dojo House, and is now interning at Pillar. I really admire how she is constantly executing on new things as well as her intentionality in learning about different aspects of the biotech industry——you can actually listen to a conversation we had on my podcast here.

I also recently met in-person with someone who I’d describe as a prolific builder. She is fluent in technologies like blockchain, Machine Learning, Brain-Computer Interfaces, and more… you may as well just watch her video building a microfluidic device for a Stanford professor. From Ananya Chadha, I admire her humility and ability to learn anything she’s curious about.

Last but not least, Maria Astolfi—Brazilian PhD student at UC Berkeley, head of iGEM Design League, previous Ginkgo-er… there’s no doubt that her passion for synthetic biology. I identify myself with her in many ways and hope I can follow some of her steps to grow a better world with biology!

If I didn’t mention you, it’s because of my urgency to publish this article—which I’d been saving for >1 month!—AND I’d LOVE to interview you for my podcast or even to continue spreading inspiration about women doing science.

Dear 21st century people,

Recently a mentor of mine asked me if I would rather live in a world in which I’m the smartest person or the dumbest person. We can carefully use the nature of this question to make a point in gender equality: would you rather live in a world in which only people your gender do science or in which everyone is allowed to?

This is a matter of ego. Men who still believe in the stupid story should realize that many evolution-shaped conducts that helped our ancestors survive in prehistory can kill us in the 21st century.

Culture forbids, biology enables. Neglecting 50% of the population is not going to help us solve some of the world’s biggest problems. If 10 woman could push humanity forward, so can the other 7+ billion… right?

La vie (not) en rose (yet)

One thing is to say that women make up 47% of total employees at biotechs or that 50% of biology PhD students are female in the developed world. Then what about women in developing nations? What about the c-suit positions? What about the biotech founders and university faculty members?

I can most easily speak for the place where I come from. Though women represent 60% of people who get a degree in Latin America, only 11% of them study STEM-related careers. More worrisome, in countries like Brazil only 18% of women who study biotechnology careers actually end up joining the biotech workforce.

Let’s talk about founders. While the number of women in life sciences increased by almost 175% between 1993 and 2015, an Insider analysis of 182 biotech and pharma companies revealed that 92% of CEOs are men. Further, other studies show how at least 95% of Harvard and MIT biotech founders are male, as are 90%–95% who serve on the boards of directors and advisory boards.

In March of 2021 I did a consulting challenge for the United Nations on how to bring more women into the digital economy in developing nations. If one thing became clear is that gender roles are still a thing and as women try to climb the corporate ladder, they definitely have it harder than men to balance “work and kids”. Male bosses know this so they think twice before promoting woman despite their talent. Hence the embarrassingly tiny percentage of women in high job positions.

A similar tendency occurs in academia. In a study with 127 subjects, science faculty from research-intensive universities rated the application materials of a student—who was randomly assigned either a male or female name—for a lab manager position. The result? Both men and women who rated were biased against applications with a female name!

Action > activism, imo

I’m that young scientist I was answering the questions for. Despite not having being born in a first-world country, I’ve have had access to good education and a wifi connection. I think that if governments in countries like mine could put more effort into those two things, we’ll see way more women around the world doing extraordinary things.

21st century policies: after reading that last study, I’m thinking more of the possibility of gender-blind hiring. Still, I wonder what you would do to help women who want to reach the c-suit while taking care of a family.

Males: my asks for you are to be as respectful as you’d be to any other human being and to remember that you don’t need to seek diversity for diversity’s sake. Recognize women for who they are as a person and for their work, not just for being women. This helps us too :)

For women who do science: just do extraordinary things. That’ll be the best way to break the stupid discourse in other men and women’s heads. Show younger girls that they can do science, by doing science.

PS: each essay I write is work in progress for me. I’d love to know your thoughts :)